Considering the Effectiveness of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) in Indonesia

In a significant step towards improving public health and enhancing the health industry, the government has enacted Government Regulation No. 28 of 2024 (Peraturan Pemerintah), which introduces comprehensive measures to address the nation's health challenges. This policy imposes restrictions on advertisements, particularly affecting the processed food and fast-food sectors, which often exceed the maximum limits for certain ingredients. The regulation will not only impact the health sector but also have a ripple effect across various industries.

While there is ongoing discussion and concern about the potential introduction of excise taxes on processed foods, which could impact pricing and consumption, this idea remains contested. Some ministry officials argue that implementing excise taxes on processed foods might not be effective and requires further examination before any decision is made. Although excise taxes have not yet been implemented due to ongoing debates among ministries, the possibility remains. Currently, the regulations dictate that any party involved in the production, import, or distribution of processed foods, including ready-to-eat products that exceed specified limits, is prohibited from advertising, promoting, or sponsoring activities targeted at specific times, locations, or demographic groups. This measure aims to reduce the consumption of unhealthy food options by limiting their exposure and appeal.

The reason behind these promotional restrictions is deeply rooted in Indonesia's broader public health concerns, particularly the alarming rise in diabetes cases. The GlobalData Consumer Survey (2021) shows that Indonesia has the highest consumption rate of sugary packaged beverages in the Asia-Pacific region. This preference for sugary drinks has resulted in a dramatic increase in diabetes cases, with children being affected at a rate 70 times higher than before. Diabetes is a major contributor to various serious health conditions such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and kidney failure. These conditions collectively cost the National Health Insurance (JKN) program a staggering 21 trillion rupiah in 2022. The surge in diabetes cases has prompted the government to rethink their approach to limiting sugar consumption in Indonesian society. By curbing the promotion of unhealthy foods, the regulation aims to address this pressing health issue, ultimately reducing the burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and fostering a healthier population.

The government has taken this matter seriously by enacting regulations that include stringent sanctions. These sanctions range from written warnings to product recalls and even the revocation of business licenses. Additionally, the House of Representatives has established a Working Committee (Panja) for the Supervision of Processed Foods and Ready-to-Eat Products with Sugar, Salt, and Fat Content. This multi-tiered enforcement approach underscores the government's commitment to upholding public health standards and holding companies accountable.

Implications for the Food and Beverage Industry

Indonesia is striving to meet its Enhanced-Nationally Determined Contribution (E-NDC) target by 2030. The latest target, E-NDC raises the emission reduction goal to 31.89% unconditionally and 43.20% conditionally, with the ultimate aim of achieving net zero emissions by 2060.[1] In other targets, Indonesia is planning to reduce the use of fossil fuels and increase the use of renewable energy. The Indonesian government has set a target for the renewable energy mix to reach 23 percent by 2025. However, the current national renewable energy mix is only at 12.3 percent.

To fulfill their target, Indonesia has undertaken several initiatives to reduce emissions. One example is the carbon credits scheme, which, although still in its early phases, represents a significant step towards incentivizing emission reductions. Another effort is the introduction of carbon taxes. Although not yet implemented, this measure is viewed as a strategy to create a more competitive carbon credit market and to encourage industries to become more sustainable by adopting clean energy solutions.

While the initiative seems ideal for reducing emissions, it is still in the early phases and has yet to be fully implemented across the entire industry. The carbon credit market in Indonesia is still not competitive and currently implemented a cap and trade mechanism only specifically for the electrical industry to support state-owned electricity company (PLN). Meanwhile, the carbon tax is still in progress, with regulations being developed by the Ministry of Finance.

With these efforts, Indonesia still lags behind in reducing emissions. In 2022, Indonesia ranked among the top six countries with an emission level of 1.981 billion tons per year. Additionally, in 2022, Indonesia's carbon emissions amounted to 700 million tons per year. The energy and transportation sectors contribute 50 percent of the emissions in Indonesia. While air quality has worsened, Indonesia is still seeking the best ways to reduce emissions without negatively impacting the economy. To reduce emissions, Indonesia plans to fully implement CCS projects by 2030, with several investors already committed to supporting the initiative.

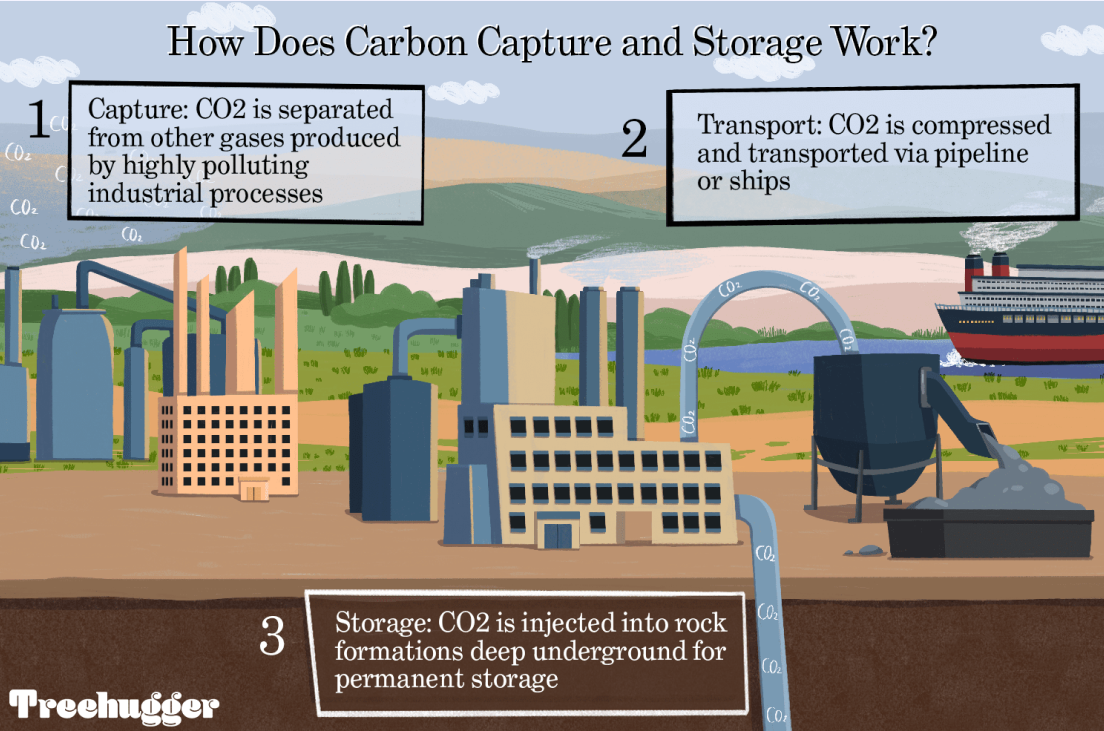

But the question still persists: how effective is carbon capture and storage technology in reducing emissions?

[1] Enhanced Nationally Determined Contributions (ENDC), Kementerian ESDM (2022)

How effective is Carbon Capture and Storage Technology?

Skepticism about CCS has been growing since the introduction of this technology. Its effectiveness is still in question, and it is often seen as impractical and expensive for industries to adopt. This has led to concerns about its viability as a long-term solution for reducing emissions.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), even if CCS technology reaches its full projected potential, it will contribute only about 2.4% to global carbon mitigation by 2030.[2] CCS is seen as an expensive and unproven solution that detracts from broader decarbonization efforts while enabling the oil and gas industry to continue operating without significant changes. The disagreement over CCS is strongly voiced by environmental NGOs, who worry that the industry will continue to depend on fossil fuel energy by relying on these technologies. Meanwhile, industries expect that the cost of CCS will be lower than the cost of emitting CO2. However, the latest tests of two CCS projects in the US have shown that while technically feasible, CCS is not economically viable for use with coal.

The ambition for CCS continues to grow globally, such as countries like the US and Canada, which are investing in these projects with the goal of significantly reducing emissions by 2030. The European Union has also implemented robust regulations for CCS, establishing a framework for its implementation across various industries. This growing ambition is driven by efforts to lower the cost of CCS for industries through subsidies, making the technology more viable and accessible. While countries view CCS as an emerging technology, the carbon credit market and carbon tax remain the most effective methods for reducing emissions. CCS serves as a supplementary technology, with the revenue from carbon taxes used to subsidize CCS projects, supporting their development as a green initiative.

[2] Enhanced Nationally Determined Contributions (ENDC), Kementerian ESDM (2022)

Towards the Implementation of CCS in Indonesia

Indonesia has created regulations to enhance the use of CCS through collaboration with other governments and private entities.[3] The goal of CCS is to help industries fulfill their responsibility in reducing emissions by providing exceptions for those that implement CCS technology in their production processes. The plan aims to have these projects fully implemented by 2030, with two investments from foreign countries already in place. While the effort seems to be working in favor of the industries, there is still a big question about how effective Indonesia's method will be in tackling climate change issues.

CCS is seen as an advanced technology to reduce emissions, but it cannot be relied upon as the sole solution for industries to cut their emissions. Indonesia still needs to be aggressive in implementing the two most effective methods to date: carbon tax and carbon trading. Learning from the experiences of other countries, especially the US and EU, reducing emissions requires industries to transition to cleaner energy technologies. By aggressively implementing carbon tax and carbon trading initiatives, Indonesia could ensure that tax revenues are allocated to green projects. Funding CCS projects with revenues generated from carbon taxes could effectively incentivize emission reduction among industries and facilitate the development and deployment of climate mitigation technologies, such as CCS. This proactive approach would reduce reliance on industry funding or foreign investments for CCS implementation, strengthening Indonesia's commitment to sustainable development and climate action.

The implementation of CCS should specifically target industries with the highest emissions, such as steel and cement production. These sectors are crucial targets for CCS implementation to help achieve the goal of net-zero emissions by 2060, while also pushing them towards cleaner practices. CCS represents a viable solution for heavy-emitting industries to develop sustainable pathways. To support these efforts, the government could subsidize CCS projects using revenue generated from the carbon credit market and carbon taxes.

Tackling climate change is a complex issue that varies among countries. As one of the largest emitters, Indonesia must address this challenge by adopting the most effective methods already in place. While considering CCS as a solution, Indonesia aims to expand projects that reduce emissions without negatively impacting industries or the economy as a whole. However, these efforts are often viewed as insufficient. Learning from other countries, Indonesia should prioritize the implementation of sustainable energy by integrating carbon tax and carbon trading mechanisms. CCS can then be treated as one of several green projects rather than a singular solution for emission reduction.

[3] Regulation for CSS in Indonesia has been implemented with PP No. 14 Tahun 2024 tentang Penyelenggaraan CCS